From the “Mensōre Okinawa” (Welcome to Okinawa) sign hanging over the gates at Naha Airport arrivals to the name of local dishes and drinks – “gōya chanpurū” (bitter melon stir-fry), or sanpin-cha (jasmine tea) – many words used daily in Okinawa are in fact not Japanese: they come from Uchināguchi, a language that was spoken on the islands long before modern Japanese.

At the crossroads of maritime routes in east and southeast Asia, the independent Ryukyu Kingdom that ruled over Okinawa islands until the late 19th century absorbed many influences from the neighbouring countries, especially China and Japan. It also developed a strong sense of identity, and many unique traditions that still endure today. Uchināguchi – or “Okinawan” as the language is commonly referred as in English – is part of that identity.

One of the many Ryūkyūan languages

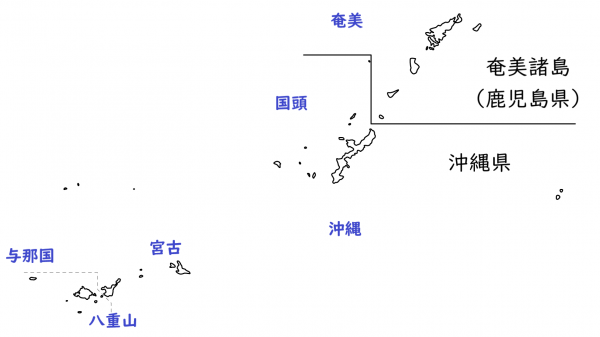

Etymologically, Uchināguchi is the language of “Uchinānchu”, the people of “Uchinā”, the native word for “Okinawa”. More precisely, Uchināguchi is the variety spoken in the central and southern area of Okinawa’s main islands (around Naha), as UNESCO recognizes 5 other languages in the Ryukyu Islands, each with a number of dialects. Although all Ryukyuan languages share a common ancestor with modern Japanese, they are not mutually intelligible. As many features that have disappeared in Japanese have survived in the Ryukyuan languages, they are actually a goldmine of information for researchers looking into the evolution of Japanese language. Moreover, with Okinawa becoming a trendy destination in the 1990’s, many Uchināguchi words have made their way into the standard Japanese lexicon.

Preserving the local languages

Yet regional languages have not always been widely accepted. After the Ryukyu Kingdom was annexed by Japan in 1879, local culture and languages were suppressed in the name of assimilation. During World War II, Ryukyuan languages were made officially illegal, although in practice the older generation couldn’t speak standard Japanese. Until long after the war, students caught speaking the Ryukyuan languages were made to wear a “dialect card” (hōgen fuda) as a method of public humiliation. With the advent of television after the war, standard Japanese slowly prevailed over native languages.

Today, Ryukyuan languages are almost exclusively used by the elderly and in multigenerational households, and in 2009 UNESCO labeled all 6 of them, including Uchināguchi, as “endangered”.

In the recent years, there have been attempts to bring the languages to a younger audience, and to advertise it as an important part of Okinawan identity. Since 2006, Ryukyuan languages are commemorated on September 18, which has been proclaimed “Shimakutuba no Hi” (“Island Languages Day”). They also survive in a lot of traditional activities, such as folk music, folk dance, poem and folk plays.

Today as more Okinawan embrace their regional identity, Uchināguchi is becoming trendy again. It is everywhere on signboards, menus, and souvenirs.

It can also be a great way to break the ice with the locals! Here’s a useful guide for you to try and communicate in Uchināguchi. You are sure to make new friends!

Here’s a quick Uchināguchi lesson from our two Tourism Ambassadors. Make sure to turn the subtitles on!

| Hi! | Haisai! (men) Haitai! (women) |

| Hello! | Chuu uganabira! |

| Goodbye! | Mata yaasai! (men) Mata yaatai! (women) |

| Thank you! | Nifee deebiru! |

| Cheers! | Karii! |

| Thanks for the food! | Kwatchii sabitan! |

| Oh my god! | Akisamiyo! |

| It’s delicious! | Maasaibiin! |

【Food】

| Chanpuruu (sometimes spelled champloo) | Stir-fry |

| Tebichi | Pigs’ feet |

| Maasu | Salt |

| Jiimaamii | Peanut |

| Hiijaa | Goat |

【Expressions】

| Nuchi du takara. | Life is the real treasure. |

| Ichariba choodee. | We became like family from the moment we met. |

| Nankuru nai sa! | Hakuna matata! |